I’m trying to blog more actively, and I figure that a good way to start is to write small pieces about research that I read.

A new working paper by Yang et al. (2021) suggests that interventions that aim to improve awareness about HIV/AIDS can backfire by reducing testing rates.

They start with a theoretical argument. People at higher risk are more likely to get an HIV test. Others might see the decision to get an HIV test as a signal of high risk, and hence choose not to interact with them (stigma). The level of stigma increases if HIV is perceived as more transmissible. Anticipating this, people at higher risk become less likely to take a test as perceived transmissibility increases.

This is an incomplete model in many ways. For instance, a negative test – if that information is made public – could cause people to stigmatize someone less than the average person even if they’re at higher risk, because they aren’t HIV-positive right now. That is one incentive to test. Another is that people might internalize some of the costs of transmissibility – so if, for example, you’re in a relationship, then more transmissibility might increase the benefit of knowing your test result, so you know if you need to take precautions. In such environments, it’s also possible that others can tell whether you’re at high risk through ways that aren’t just testing information.

To help fix some of these problems, they look at a specific PEPFAR-supported program called Força à Comunidade e Crianças in Mozambique. It is “a community-level program that implements home visits to households, as well as complementary interventions in communities and schools.” They test the program’s efficacy in an RCT involving 3,700 households among 76 communities. Half the communities were in a treatment group and half were in a control group, and, among the former, a subset was given stronger encouragement to participate. Using administrative data on HIV tests, the study compared households that received stronger encouragement from within the treatment group and households in the control group on the likelihood of receiving a test two weeks after the endline survey.

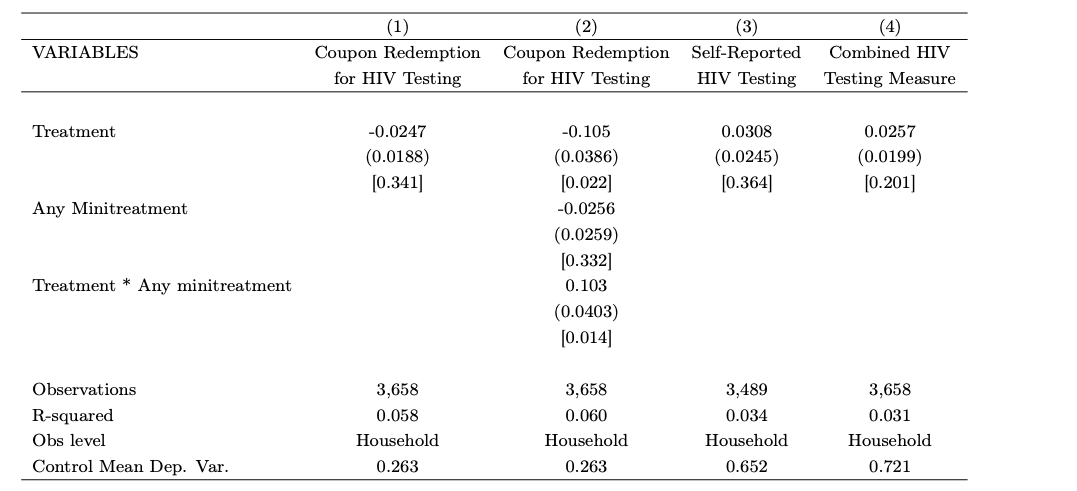

They found that “the FCC program has a negative effect on HIV testing: -10.9 percentage points, relative to a base of 26.3 percent in the control group.” Indeed, treated respondents became more likely to believe falsehoods about transmission. But this data doesn’t prove the theoretical argument the paper outlines. They used a different strategy to do that: “Immediately after the endline survey, our research staff then randomly assigned households to a set of ‘minitreatments’ aimed at encouraging further HIV testing, or a minitreatment control group. The different minitreatments provide HIV-related information, seek to alleviate concerns about HIV-related stigma, and provide additional financial incentives for HIV testing.” They find that minitreatments that improve information or reduce stigma can help offset the negative effect of the treatment on testing.

The basic results are here (from table 2, page 40):

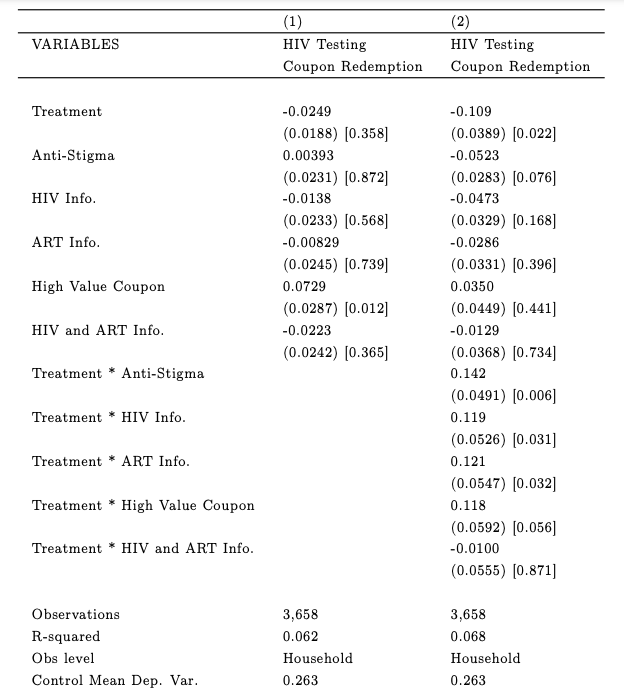

This doesn’t distinguish between minitreatments, so here’s a table looking at individual minitreatments (from table 5, page 42):

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the financial incentive – the high-value coupon – has the largest effect on coupon redemption, but the anti-stigma treatment also seems to have a small positive effect. The other minitreatments seem negative in terms of testing, but they do seem effective at offsetting the negative effects of the treatment.

This research also raises some potential ethical concerns about RCTs – is it ethical to subject people to treatments that could be negative? I’m not compelled by the ethical objection to RCTs here, since this is a program that exists anyway and information about how we respond to it is useful. I’ll also note that HIV testing is only one variable, so we can’t automatically conclude the treatment is negative.

I found this paper an interesting example of well-intentioned policies not aligning incentives well enough.